Since the Notre Dame fire, I’ve had lots of interesting conversations and fielded many pertinent questions. I thought instead of endlessly repeating myself, I should write some of this stuff down. Here goes:

What exactly was lost? How do we fix it?

The cathedral itself took the brunt of the damage: most of the artwork and relics were moved to safety. The roof is very obviously gone, as is the spire which sat on top of it. The vault also sustained damage. I’ve spotted at least three major holes in the few pictures that have been posted so far.

The problem with this short summary, and with the pictures that were posted, is that they paint a picture of “minor” damage. This is likely not the case. First, the obvious: there is currently no roof on the cathedral, and the vaults that still stand are weakened. Any rain and wind is a hazard.

Even worse: every piece of the masonry needs to be assessed. Yes, it’s mostly still standing, but the fire just ended, and the masonry is still cooling. The limestone the cathedral is built of is sedimentary rock. This means it is porous, friable, and prone to cracking. When all that water was poured on the structure, it likely caused some thermal shock. This means some areas are probably in need of major shoring.

Plus, the stained glass is likely weakened too. The lead holding the pieces together didn’t fail, but I’d be surprised if some of it wasn’t weakened and partially melted. Stabilizing the rose windows will be a gigantic effort all by itself.

There’s also the rubble on the ground. This isn’t stuff you can just toss in the landfill. Every piece needs to be assessed, to see if any of it can be reused.

So, we are looking at a giant, ridiculously complicated jigsaw puzzle, while also working against the clock, and trying to fix dozens of things at once, even though fixing one might well hurt another. And to top it all off, not all the pieces are still there.

Can we rebuild the same?

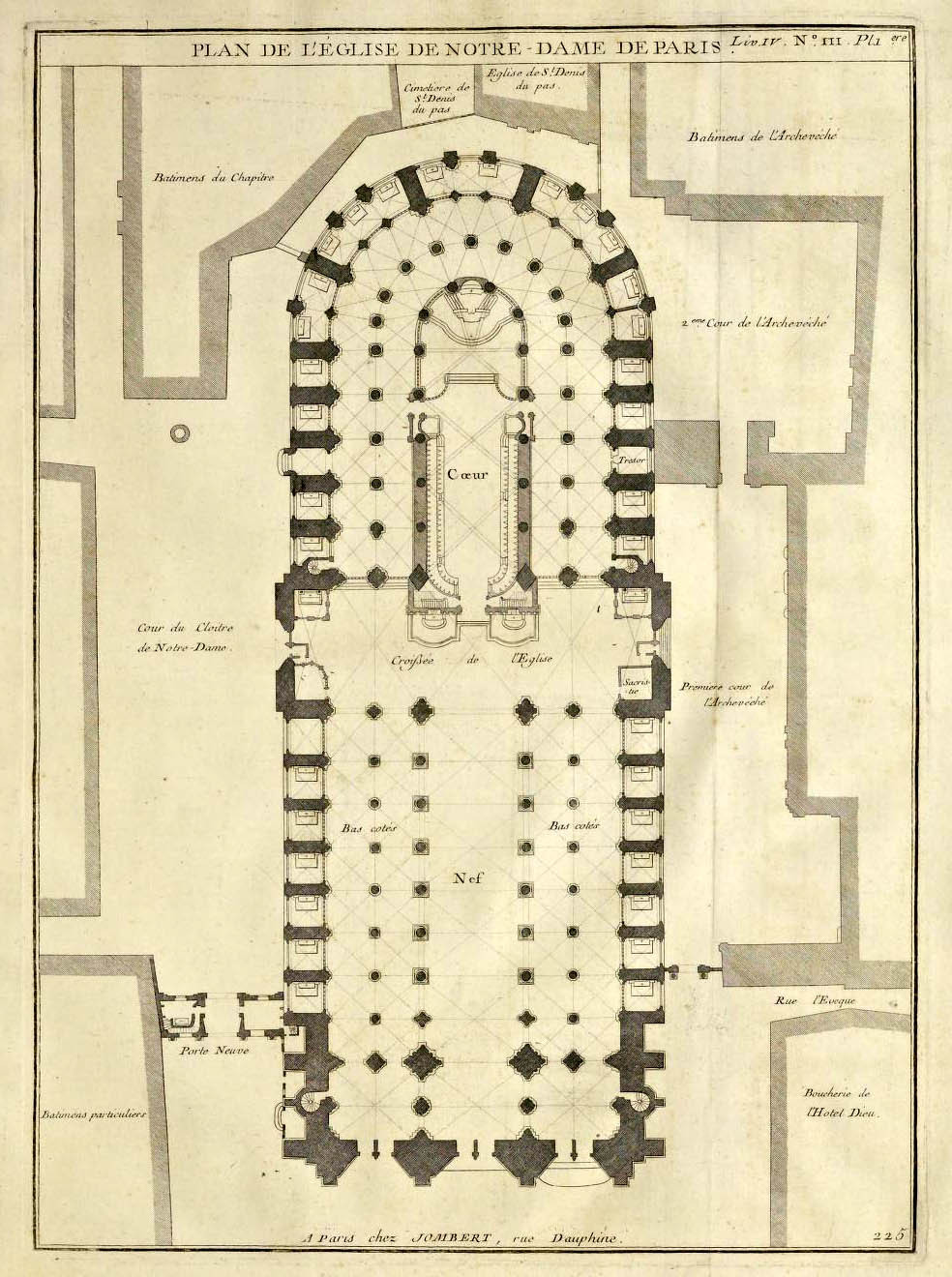

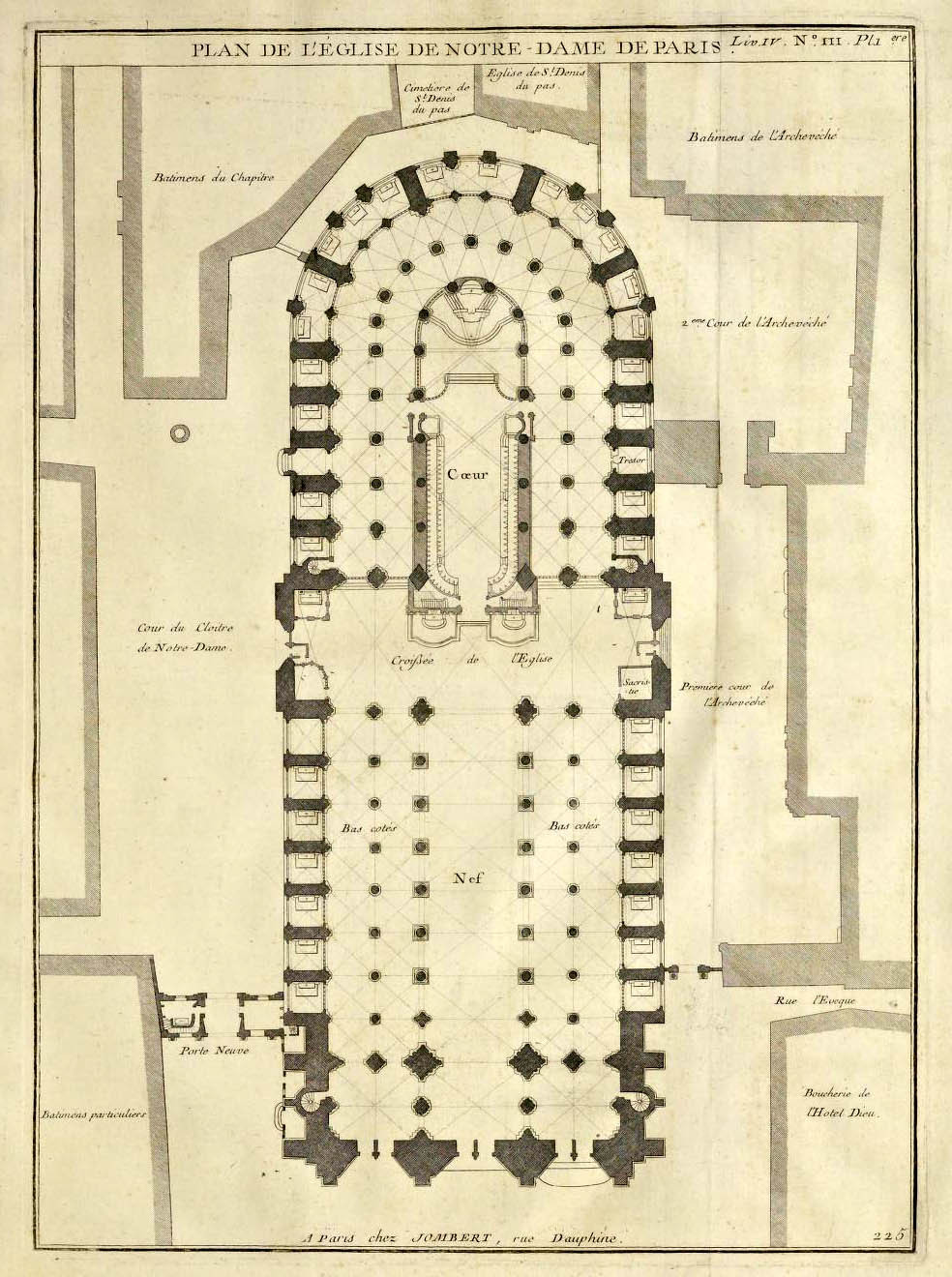

We do have complete, comprehensive documentation of the cathedral. Notre Dame is one of the most well-documented buildings in the world. It’s been measured and drawn both through traditional paper-and-pencil means and with lasers and VR. This is an enormous boon, and makes it at least theoretically possible to rebuild the same.

The main problem will be the roof support system. The way the cathedral was built is very typical: the walls are masonry, and to create that soaring space, the weight of the walls is carried outward with the flying buttresses. The internal space is finished at the top with gothic vaults, which are also stone. They look gorgeous, and create the cathedral-specific acoustics, but they are not the roof. All they are meant to carry is themselves.

This means that above the vaults, there is a truss system which in turn carries the roof. This truss system was built of 400 year old hardwood. [think about that for a second! Those trees were likely planted in the 700s.] Simply put, we don’t have wood like that available anymore. Some have talked about finding comparable wood from the Baltics, but I think that’s a terrible idea for multiple reasons:

- Even if we manage to find enough wood, it won’t be as good as the wood used originally. The weather was noticeably colder in the Middle Ages, which means smaller growth rings, which means stronger, more fire-resistant wood.

- It burned. I understand wanting to use the same materials, but we now know how to build to minimize fire risk. The roof was always the most flammable part of a cathedral, so why not build safer now that we can? A steel truss, perhaps also with argon gas in between the vault and roof would be much safer.

- No one will see this anyway. Unlike other parts of the cathedral, replacing the structural support elements will be covered up. Some people find new additions to old buildings visually jarring, but for this application, no one needs to look at it.

I’m not the only one who thinks this, by the way. For another perspective and great explanation of the roof, check Witold Rybczynski’s blog: https://www.witoldrybczynski.com/architecture/fire-in-the-cathedral/ (Thanks, Dr. Henry, for sharing!)

Should we rebuild the same?

That’s another difficult question. Notre Dame actually has well-documented history of change. The man who made much of that change happen is Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. Incidentally, Viollet-le-Duc is also one of the fathers of preservation theory, with Ruskin and Morris rounding out the Big Three.

To poorly paraphrase Viollet-le-Duc’s view, he thought that if one has the technology to build better than it was, one should do so. And he did that for lots of buildings, including Notre Dame itself. The spire – or flèche (arrow) – was his design. He built it of lead-covered wood, and the design of it, as well as other parts of the cathedral that he “renovated” say much more about Viollet-le-Duc than what came before.

A spire must be rebuilt, but what should it look like? Some are now advocating for a “new” design. Currently, it seems that there will be a design competition. This seems like a very bad idea to me. Why not just go with Viollet-le-Duc’s idea, and rebuild, but with more durable materials and technology? A truly new design would be jarring on Notre Dame. Not to say this hasn’t worked in other contexts: the Pyramid of the Louvre is a case in point. But Notre Dame isn’t just a cultural touchstone, but a religious one. It shouldn’t be trendy.

At least this contest idea has also spawned some hilarious responses, but I’m still cringing at how badly this could turn out.

France gave New York the Statue of Liberty. Why doesn’t it return the favour? pic.twitter.com/vzkyxA57qR

— Olly Wainwright (@ollywainwright) April 17, 2019

What about the timeline?

Another complication. This is not just an important building, it’s also the largest single tourist draw in Europe (yes, even more than the Eiffel Tower.) The French president, Emmanuel Macron, has made it clear he wants the cathedral “finished” by 2024. Why then? The Olympics. Paris is hosting in summer 2024. Hence, the cathedral needs to be open by then.

That said, I don’t believe this is a realistic deadline, at least not to actually “finish” the cathedral. Stabilize? Open parts of it to the public? Sure.

But finish rebuilding the roof? This is a laughably short timeline. Just fully checking the structure for cracks will probably take a year. This is *before* remediation, before design competitions can be completed, before accepting plans to rebuild, before phasing the construction steps.

I think 20 years is more realistic to complete the work. And honestly, this is fast by cathedral standards. Cathedrals took – and still take – centuries to build. Spending a couple decades to fix one isn’t that long by comparison.

What about the Church?

You might wonder what the Church wants to do about this and be surprised to hear that they don’t really get a say. France isn’t like the U.S. Churches aren’t protected in the same way they are by the 1st amendment here. Furthermore, Paris owns all churches in the city built before 1905, except Notre Dame, which is owned by the Ministry of Culture. In other words, the Architect des Bâtiments de France is the one in charge here, not the Church.

Except I don’t think that’s realistic either. While nominally in charge, I can’t imagine that the Ministry of Culture will be able to weather bad press. There will be extreme pressure from the presidency to make this a positive, fast moving reconstruction effort. After all, France is politically unstable right now, and the funds made available for the reconstruction have further incited fury over income inequality.

This is yet another reason why I’m worried about Notre Dame. I expect that the process will be significantly rushed in order to placate the public. That will not make for good quality construction.

What does this all say about preservation?

I don’t want to oversimplify the situation, but I do think there are a few clear takeaways already emerging.

First, people care about the built environment and history. The visceral reactions to the Notre Dame fire came not just from Catholics but from people of all cultures. It’s awful to think that losing something brings its importance to the forefront, but let’s be honest: that’s human nature. Losing Penn Station famously spurred American preservation. Perhaps this (hopefully more temporary and smaller) loss will also bring new passion and growth to the field of preservation.

Second, this calamity has emphasized that preservation is very complicated, and is intrinsically multidisciplinary. Politics, fire suppression, dendrochronology, law, documentation, stone masonry, finance, you name it. It’s all there. Perhaps this will discourage some, but to me, that’s exactly what makes preservation endlessly interesting, and worth pursing. Unfortunately, most people want quick resolution, and falsely believe that throwing money at a problem will solve it. I hope that most people will show patience in this case, but I won’t hold my breath.

Third, the response to this fire will likely be an emblem of preservation in the future. Dominating preservation philosophies have evolved a great deal since Viollet-le-Duc, and are likely to keep changing over time. This building will hopefully stand significantly longer than most buildings we preserve today. The way we respond to this fire will be visible in the built environment for centuries to come. It is an enormous responsibility. I’m not opposed to some levity (Like St. Thomas, the patron saint of architects, with Viollet-le-Duc’s likeness) but there’s also a real risk of being too fashionable and rushed. The last thing I want is a “it’s so 2020s” reconstruction. Ideally, the palimpsest that is Notre Dame will be even richer in layers and meaning in the future, rather than reduced by this fire and its aftermath. There is certainly enough money to do so. Now all we need is the will and the effort. Let’s get to work.